Workers stacked pews on either side of the church to get to the floorboards to remove then and replace damaged

joists and boards. (Stephen M. Katz photo)

Refurbishing project provides glimpse of past

By G.W. POINDEXTER

H-P Staff Writer

The prosperous farmer, headed for church in the early 1700s, carried a silver Spanish coin to put in the collection plate. As he stood in the yard in front of the wooden frame building, he dropped the coin and couldnít find it.

Alastair S. Macdonald came across it several weeks ago, at least 250 years after the planter lost it, if his theory of how the money went astray holds true. He excavated under the floor of Fork Church, an Episcopal church on Route 738 that dates from the 1730s.

Macdonald, an accountant in Williamsburg whose parents go to the church, also worked on digs at Scotchtown and in Williamsburg. At Fork Church, he worked on under the floor in stages as construction crews had it removed to replace damaged floorboards and refurbish joists.

The brick building is one of the oldest churches in the county. But the building was the second on the site. An earlier wooden building also stood there, according to parish records. The structure was known as the Chapel in the Forks, the forks being the fork of the North and South Anna rivers. It was built between 1721 and 1723.

The wooden building, 20 by 36 feet, was built to serve the western frontier of the colony. At that time, Hanover was the western frontier.

Route 738, which is used today, dates from the late 1600s and was originally a road that ran from Yorktown to Coatesville, Macdonald said. The road was used to get tobacco to port and other goods and people back from Yorktown.

For years, church members and others have surmised the frame chapel stood on the same spot as the brick one, but Macdonald doubts the theory.

"Unless it burned, they wouldn't build the church on top of the chapel, because they wouldn't have had a place to go to church," he said.

|

|

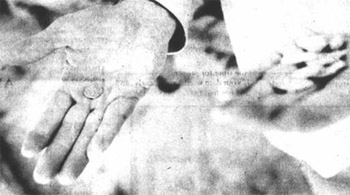

ONE LESS COIN

FOR THE PLATE

The small Spainish coin Alastair Macdonald holds in his hand seems to predate the brick building under which it was found, as do the flecks of stone from Indian arrowhead manufacture in his other hand. (Stephen M. Katz photo)

The cemetery behind Fork Church holds the dead from generations of people who went to church there. (Stephen M. Katz photo) What he does think is that the part of the yard of the older wooden building may be under the brick church.

Macdonald found the tarnished coin, which still bears the faint imprint of the coat of arms of Philip V of Spain, under a three-inch-thick layer of brick dust, which looks to be construction debris from the brick building.

"I'm confident that coin was there before this church was built," Macdonald said.

He also found several holes that could are probably post holes. Macdonald said he thinks the holes are post holes for the a fence that records indicate surrounded the wooden chapel.

"I'm comfortable those holes relate to the chapel," he said.

But he's not had time to analyze all he found, and the main function of the dig was to catalogue and map everything before the area is covered up.

The nails in the floor supports for instance, are not the kind that would have been used in 1735. That could mean the church was gutted when a renovation was done in 1835. With modern written records, such questions easily could be answered. But with sketchy,

incomplete records, Macdonald said he remains puzzled.

"A lot of questions will go unanswered," he said. "I wish I could give you answers. Instead Iíve given you questions."

|

A RICH HISTORY

|

- 1721 A wood frame chapel is ordered built at the forks of the North Anna and South Anna rivers. The church is finished by 1723, according to records of St. Paul's Parish.

- 1735 The earliest date at which people think a brick church was built near the wooden building. The date could be as late as 1742.

- 1776 Declaration of Independence signed, and Revolution follows. After the war, Episcopal churches in the former colonies fell on hard times, because people were reluctant to

attend churches that had been part of the state religion of England.

- 1835 The church undergoes a renovation that moves the pulpit to the front of the chapel. That movement signifies the increased significance of preaching and "the word" during the Great Awakening. The extent of the renovation is unknown.

|

- 1913 The pulpit Is moved back to the side of the church in another renovation. Workers found holes where the pulpit had originally been attached to the side of the church.

- 1957 Worker installing central heat in the church for the first time find brick piers under the floor. At the time the brick work is interpreted as the foundation of the original chapel,

built more than 230 years before. Click here to read the Herald-Progress article about the 1957 discovery.

- 1997 The church undergoes a renovation to replace joists and floorboards damaged by termites in past years and preserve brick work.

|

|

|

|

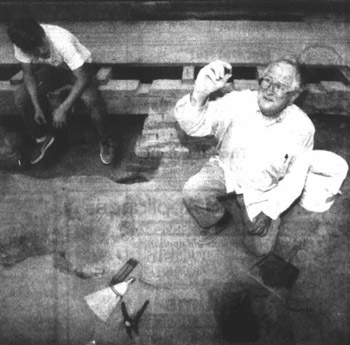

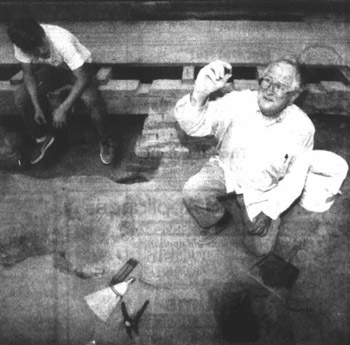

Alastair Macdonald trowels out a hole In the dirt under the floor of Fork Church. (Stephen M. Katz photo)

Religion, history intertwine

By G.W. POINDEXTER

H-P Staff Writer

In a church where at least one Revolutionary War soldier lies buried in the cemetery and where the building is older than the country, history is inextricably intertwined with religion.

At Fork Church, 125 families worship on what was once the frontier of English colonization in the New World.

"I really got in touch with the history of this place when they pulled up the floor," said the Rev. Sarah M. Trimble, the church's rector. "To see those pit-sawn joists that were hewn out in what was then the wilderness: They were people who took the time to build a marvellous space.

The church's founders were then living in wild territory as they pushed the English colony's borders further west. The English first arrived in Virginia in 1607.

"When this communion of English people arrived in Jamestown, the first thing they did was worship," Trimble said.

That element of history is what fascinates Trimble, even though she does say that what makes a church is not the building.

"Iím not a museum curator. Iím the minister of a church thatís a living, breathing, part of the body of Christ,Ē she said.

But the body of Christ needs a home, and the when the home is more than 250 years old, a little sprucing up is often in order.

The archaeological work was done while the church completes $220,000 worth of renovations.

Floors needed replacing from decades-old termite damage, and two rooms in the rear of the church needed to be revamped.

Another project at the church "pointing" the bricks requires replacing the mortar in the masonry.

The bricks of the church are laid in Flemish bond with glazed headers, a Colonial building style. But the mortar washes out from the be- tween the bricks, so it must be replaced.

It is not something that has to be done in modern buildings, but for a building more than 250 years old, it is imperative.

But the attractions of age seem to win out.

Senior Warden David Reynolds, who heads the church vestry, has only lived in Hanover for four years.

"That was one thing that attracted us to Fork Church. It gives you a good feeling to go to church and think of all the other people who have done the same thing," he said.

Alastair Macdonald holds up a small piece of broken glass from a hole dirt. The glass is probably from a wine bottle. Macdonald catalogued such artifacts for further study. (Stephen M. Katz photo) Click here to read the 1957 Herald-Progress article about Fork Church. |